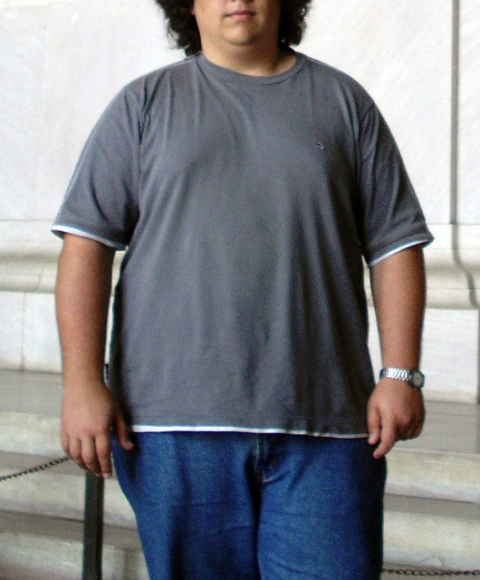

Note to young men: fat doesn’t pay

Men who are already obese as teenagers could grow up to earn up to 18 percent less than their peers of normal weight. So says Petter Lundborg of Lund University, Paul Nystedt of Jönköping University and Dan-olof Rooth of Linneas University and Lund University, all in Sweden. The team compared extensive information from Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, and the resultsare published in Springer's journal Demography.

The researchers analyzed large-scale data of 145,193 Swedish-born brothers who enlisted in the Swedish National Service for mandatory military service between 1984 and 1997. This included information gathered by military enlistment personnel and certified psychologists about the soldiers' cognitive skills (such as memory, attention, logic and reasoning) and their non-cognitive skills (such as motivation, self-confidence, sociability and persistence) which can affect their productivity. Tax records were then used to gauge the annual earnings of this group of men, who were between 28 and 39 years old in 2003. The Swedish results were further compared with data from the British National Child Development Study and the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979.

Previous research has shown only that obese young women pay a price when they enter the labor market. This study is the first to show how this pattern also emerges among men who were already overweight or obese as teenagers, but does not hold true for males who gain excessive weight only later in life. In fact, obese teenage boys can grow up to earn 18 percent less in adulthood.

"To put this figure into perspective, the estimated return to an additional year of schooling in Sweden is about six percent. The obesity penalty thus corresponds to almost three years of schooling, which is equivalent to a university bachelor's degree," the authors explain.

A strikingly similar pattern also emerged when the researchers used the specific data sets from the United Kingdom and the United States. This confirms that the wage penalty is unique to men who are already overweight or obese early in their lives.

The researchers ascribe the wage penalty partly to obese adolescents' often possessing lower levels of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. This is consistent with the evidence linking body size during childhood and adolescence with bullying, lower self-esteem and discrimination by peers and teachers.

The researchers advise that policies and programs target overweight and obesity problems, which are often more common among low-income households. This could reduce disparities in child and adolescent development and socio-economic inequalities. It could also cut persistent patterns of low income across generations.

"Our results suggest that the rapid increase in childhood and adolescent obesity could have long-lasting effects on the economic growth and productivity of nations. We believe that the rationale for government intervention for these age groups is strong because children and adolescents are arguably less able to take future consequences of their actions into account," says Nystedt. "These results reinforce the importance of policy combating early-life obesity in order to reduce healthcare expenditures as well as poverty and inequalities later in life."

© MD News Daily.