Antibodies May Not be the Key to Combating COVID-19

No evidence has been presented yet, that people could have recovered already from the illness, and if antibodies could protect one from another infection.

In April 2020, it was announced that the World Health Organization published guidance on the adjustment of public health and social measures for the then next phase of the COVID-19 response.

With the guidance, several governments proposed that the discovery of antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2, the infection that causes COVID-19, could be considered an immunity passport that would allow individuals to travel back to work, supposing they are shielded from any re-infection.

However, when the report came out, there was no evidence yet that people could have recovered already from the illness, and if antibodies could protect one from another infection.

At present, several reasons have been recently published why antibodies may not be treated as the key to combating COVID-19.

ALSO READ: Tricare Issues an Apology Statement After Telling 600k Beneficiaries They've Had COVID-19

T-Cells Found, but without Antibodies

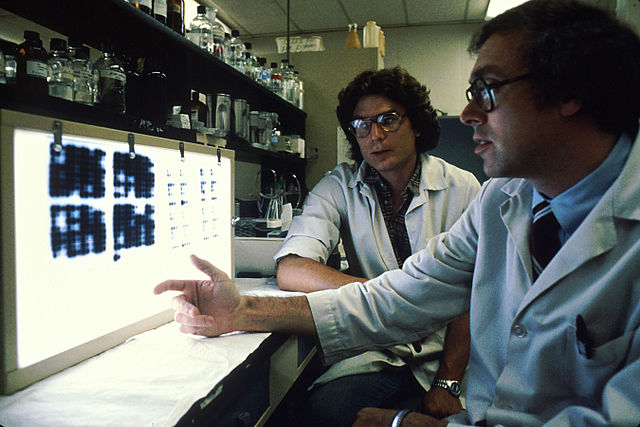

Researcher and physician, Soo Aleman, who switched from working on hepatitis B and C viruses to assess COVID-19, started to screen patients for the said infection for indications of an immune response in the body.

Sweden, Aleman's home country, which also reportedly found itself being hardly hit by the pandemic too, made the Swede physician pivot to COVID-19 study. And as she started screening patients, it was then, when things got weird.

Studies made about this deadly infection indicate that body needs to yield both antibodies, which prevents the virus from spreading.

Typically, these immune reactions take place in tandem. Nonetheless, in a subsection of people who tested positive for COVID-19, a recent report said that Aleman discovered T cells but no antibodies.

Other researchers globally found similar findings too. Reportedly, much of this work remains introductory, and researchers have no idea what it means to evaluate how effective a vaccine is, or how well individuals are shielding themselves from serious forms of illness.

One thing is turning clear though--Aleman said that antibodies might not be telling the entire story in terms of COVID-19 immunity.

DON'T MISS THIS: 75% of Recovered COVID-19 Patients Experience Heart Inflammation Months After the Illness, Research Finds

Antibodies Measurement Specific to the Virus

Report from the WHO indicated that immunity's development to pathogen through natural contagion is a multistep process that usually occurs between one to two weeks.

Essentially, the body immediately reacts to a viral infection that has a non-specific innate reaction in which macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells delay the virus's progress and may even top it from resulting in certain symptoms.

This particular non-specific reaction is followed by an adaptive response in which the body develops antibodies that particularly attach to the virus.

Antibodies are proteins known as immunoglobulins. In turn, the body makes T-cells which identify and remove other sells which the virus has infected.

Such a process is called cellular immunity. Additionally, this mixed adaptive reaction may clear the infection from the body. If such a reaction is robust enough, it may stop development to severe disease or re-contagion by a similar virus. Such a process is frequently gauged by the existence of antibodies in the blood.

Role of T Cells

King's College London immunologist, Adrian Hayday, a recent report said, is less worried. He said that even though T cells are more challenging to measure and may not stop a re-infection, they play a vital role in the ability of the body to remember previous infections and shield an individual from a serious illness.

Pointing to some new studies on COVID-19 and other coronaviruses as evidence, Hayday added, it appeared that T cells could be helpful to anyone who has the virus.

Common coronavirus immunities just the last one to two years, which is why, Duke-NUS Medical School immunologist Antonio Bertoletti explained, "sniffles and stuffiness" stay a universal and persistent part of life.

Nonetheless, the patient infested with the original SARS virus still owned the so-called memory T cells that reacted to the proteins of the virus, 17 years later.

Similar T cells responded to COVID-19, and it is something augurs well for the said virus, explained Bertoletti.

IN CASE YOU MISSED THIS: Analysis Shows Convalescent Plasma Could Reduce COVID-19 Deaths by 57%

Check out more news and information on COVID-19 on MD News Daily.

© MD News Daily.