HIV is Slowly Evolving: Study

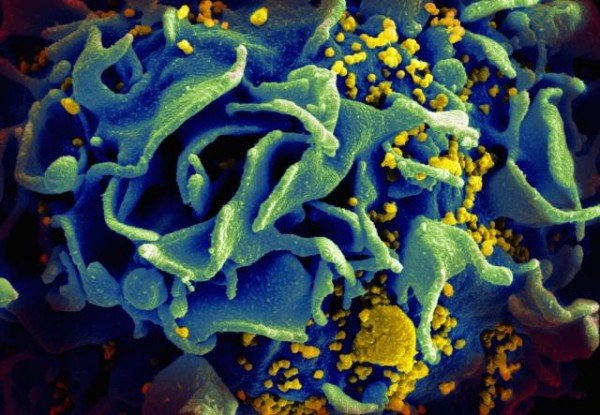

Researchers have found evidence that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is slowly adapting over time to the resistances of its human hosts, according to a recent study. The good news? The virus may be evolving so slowly that scientists are almost certain that they will have HIV beat before it can evolve to resist new treatments and preventative options.

The study, published in PLOS Genetics, details how researchers from Simon Fraser University (SFU) in collaboration with scientists from the BC Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS tracked the gradual evolution of the HIV virus as it has made into way into various demographics in North America.

According to the study, the researchers began their project by determining the genetic sequence model of HIV back in 1979. This would serve as the "original" North American HIV, as the first officially documented cases of AIDS resulted from this version of the virus back in 1981, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports.

The researchers then sequenced other samples and infection profiles of the virus all the way to current day cases of the infection. Comparing disparities between the sequencing of the virus, the researchers were able to map out how the virus was gradually evolving to better adapt to the North American auto-immune profile.

The good news is, that through this assessment, the researcher determined that the virus is adapting so slowly in North America that it stands little chance against the influx of treatment options, potential cures, and pending vaccinations that the country will likely see within the next few decades.

"We already have the tools to curb HIV in the form of treatment-and we continue to advance towards a vaccine and a cure," the study's lead author Zabrina Brumme wrote in a concluding statement. "Together, we can stop HIV/AIDS before the virus subverts host immunity through population-level adaptation."

Still, while North America may be safe, the researchers explain that other countries with greater prevalence of the virus and less access to treatment for it may be facing a higher rate of evolution, meaning that the virus will likely not be facing extinction any time soon.

The study was published in PLOS Genetics on April 24.

Apr 26, 2014 05:44 PM EDT